Institute News

- Woman inner peace and family general health seminar announcement

- The 2nd Conference of Medical Biophysics and its Applications

- Handwashing awareness

- 6th october artistic and cultural competition announcement

- leukemia Awareness Month Sceitific day

- Students Orientation Autumn 2025/26

- 6th October celebration

Students News

- GraphPad Prism as a statistical tool for biomedica...

- Tools of References Management " EndNote "

- MRI Postgraduate application procedures

- Exam Schedule Spring 2025

- The Fourth Student Conference of the Medical Resea...

- Announcement for new students, registration spring...

- Important notice for graduate students

Conferences

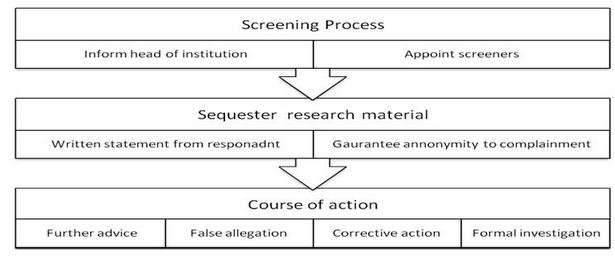

Introduction This article will demonstrate on how to respond and how to conduct an investigation of alleged research misconduct. Each institution should have a declared policy and written procedures dealing with research misconduct which are activated once an allegation of research misconduct is reported. However, it is advisable to apply this code of practice to the rather serious spectrum of research misconduct (see previous edition of EJS) especially those characterized by deception for personal gain such as data fabrication, data falsification and plagiarism. Most investigational approaches use a two-stage approach. An initial screening phase which may be followed by a formal investigative phase if the screening phase indicates to the presence of research misconduct.

Phase One

The screening phase should adopt a step wise approach involving the three levels of management when dealing with research misconduct complaints. The first level of management in university based institutions will include the head(s) of department, the next in line will be the dean of the institution, and the third level will be the president f the university itself. Initial allegations should be made to the head of the department and to the individual to whom the head of department is directly responsible (Dean) who may nominate another appropriate individual to act on his or her behalf. The head of the department and a senior member of the department (not directly or indirectly related to the incident) would act as screeners of the research misconduct incident. The complainant must be guaranteed anonymity and allowed to have a representative present at all interviews during the screening and formal investigation. The head of the institution must be informed of the allegations, all research material should be collected and sequestered and a written statement sought from the respondent (accused). The screeners will then consider the available evidence and the written statement (response) from the accused and decide to pursue one of the following courses of action: 1. Seek further advice.

2. Consider the allegation to be unfounded and dismiss the complaint. If the allegation is deemed to be malicious, the head of the institution may `invoke disciplinary action against the complainant.

3. There is some substance in the allegations but the matter does not warrant a formal investigation. Some corrective action may be recommended. In such situation, the respondent (accused) has the right of appeal.

4. There is sufficient substance in the allegation to initiate a formal investigation of the complaint.

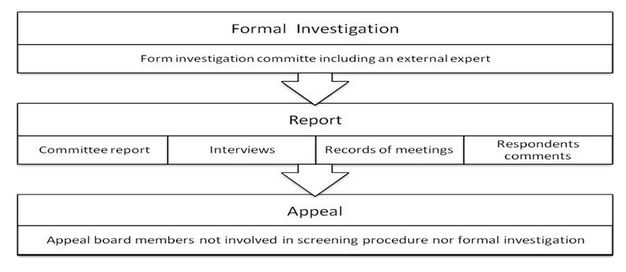

Phase Two

The formal investigation is only initiated if the screening process deems it necessary. The objective of phase two is to seek answers to the following questions: 1. What are the relevant facts?

2. Has research misconduct been committed?

3. If so, who is the responsible person or persons?

4. What is the seriousness of the misconduct? The Investigation Committee

The committee should consist of at least three people; one of whom (at least) is from outside the institution and a recognized expert in the field under investigation. None of the members of the committee should have conflicts of interest with the respondent or the case in question. The committee members must have some experience in examining evidence, interviewing witnesses and conducting an investigation. The complainant and respondent (accused) must be notified in writing that a formal investigation is to be undertaken. The respondent (accused) must be able to object in writing to any individuals appointed to the investigation committee. Accordingly, the head of the institution may decide to replace the challenged person with a qualified substitute. The Investigation The investigation will include examination by the committee of all documentation, including computer disks, materials, proposals, publications, correspondence and memoranda. Interviews will be conducted with all individuals involved in making the allegations and other individuals who have information regarding key aspects of the allegations. A word for word record of these interviews must be prepared by the secretariat and approved by interviewer(s) and interviewee(s) to ensure factual accuracy; this record must be included as part of the investigation report. The Report The report must state how the investigation was conducted, describe how and from whom the information relevant to the investigation was obtained, state the findings and explain the basis for the findings. Agreed word for word reports of all interviews must be included in the report as an appendix. The respondent (accused) or respondents against whom the allegations have been made will be given a copy of the evidence considered by the investigation committee and a copy of the report. The respondent (accused) must be given an opportunity to comment upon the report in writing. The respondent (accused) may request a meeting with the investigation committee to allow the respondent (accused) to challenge statements which he or she believes to be unsubstantiated. A record of this meeting with the respondent's (accused) comments on the report shall form part of the investigation report and will be provided to the head of the institution. The investigation committee will report its findings to the head of the institution and the head of department of the person against whom the allegations have been made. Outcome Should the allegations be proved, the head of the institution with the appropriate person (e.g. head of department or research group) should decide what action needs to be taken. This may include informing relevant authorities such as the president of the university, the appropriate professional bodies, the relevant grant awarding body, editors of all journals in which the respondent has published articles especially those related to the research misconduct. Action may also be taken to revoke a degree or other qualification obtained wholly or partly through misconduct in research relevant to that degree or other qualification. Other disciplinary action may be warranted. Even if the respondent resigns from the institution before completion of the investigation, the investigation must be completed by the institution and a report submitted to the head of that institution. Appeal The respondent (accused) may appeal following either the screening or following investigation. An appeal board should be appointed within a short set time from the receipt of an appeal by the respondent (accused). There should also be a time limit for completion of the appeal. The appeal board will consist of two or more individuals who were neither members of the initial screening procedure nor of the investigation committee. The head of the institution will notify the respondent (accused) of the proposed appeal board membership. The appeal report must state how the appeal was conducted, describe how and from whom further information was obtained, state and explain the basis for the findings. The head of the institution will then take appropriate advice and decide on the basis of the appeal report whether to endorse, amend or overturn the conclusions of the screening or the investigation. The head of the institution will notify the respondent (accused) in writing of the outcome of the appeal board and will provide a copy of the appeal report and evidence considered by the appeal board. The decision of the head of the institution shall be final. Manuscript resources Committee for Publication Ethics (COPE): www.pubicationethics.org

International Conference of Harmonization: www.ich.org

Serious Research Misconduct

Fabrication

Falsification

Plagiarism

Failure to get ethical approval

Hiding missing data

Undeclared omission of outliers

Excluding data on side effects or adverse events

Human subject research without informed consent

Publication of post hoc analysis without declaring that they were post hoc

Gift authorship

Ghost authorship

Dual publication

Not disclosing conflict of interest

Failure to publish completed research

Not performing a literature review before starting a new research

Minor Research Misconduct

Diagnosis of research misconduct

Research misconduct can be identified during conduct of research or during the process of its publication or even after its appearance in reputable journals. A large proportion of research misconduct is identified through whistle-blowers. A whistle blower could be a colleague, research partner, research nurse, or even the research subject. The position of a whistle-blower is usually difficult and traumatic as he or she, in many situations, is met with little public gratitude or suspicion of acting from a point of professional jealousy. The diagnosis of research misconduct during its progress should be done through a formal process of research monitoring which is an essential component of good research practice. It should be conducted by authorized individuals trained to do the job in collaboration with the concerned research ethics committees and sponsors of the research project. Research misconduct is usually spotted through research site visits, examination of returned clinical trial materials, examination of case report forms, patient diaries, and or laboratory note books. Examples of signs that research monitors sometimes take especially in clinical trials indicating the presence of some irregularity are (the list is not exhaustive): 1. Work done during holidays.

2. Bulk completion of records on the same day.

3. The use of the same pen for a large number of records.

4. Lack of variation in data.

5. Similar handwriting in data entry forms, diary cards and informed consent forms.

6. Absence of original laboratory or pathology documents.

7. Similar investigation results such as ECG tracing.

8. Sudden appearance of missing data at previous monitoring visits.

9. Same pattern of usage or return of trial materials in both arms of a clinical trial. Editors of medical journals can sometimes spot research misconduct at time of publication. This usually includes plagiarism or dual publication. The faultless manuscript with perfect design and perfect English language is one sign that the editors in the Egyptian Journal of Surgery have found many times to indicate serious plagiarism. However, data fabrication and falsification are more difficult to diagnose at this time but some work is being done worldwide to develop mathematical methods for its diagnosis. Prevention of research misconduct An intelligent and effective strategy for dealing with research misconduct is that of prevention. The first step in research misconduct prevention is the promotion of good research practice as those proposed by the Joint Consensus Conference on Misconduct in Biomedical Research in 1999 (table 2). The second important step is when new researchers join an institution; it must be made clear that misconduct in their research will not be tolerated. Third, the researchers should be given a guide or manual on good research practice that defines their responsibility and also that of their supervisors. Fourth, all researchers should attend an induction course on the basic principles of research. Fifth, regular meeting should be conducted between researchers and their supervisors. Sixth, free access to research raw data for all participants concerned. If such an environment is created researchers will be less liable to commit any form of research misconduct. Table 2. Promoting good research. • Affirming a culture through example in which honesty and integrity are expected of every individual and misconduct is not tolerated.

• Through education, training and vigilance from the outset, starting with the undergraduate entry and continuing through life-long learning.

• Ensuring formal training of all supervisors of research.

• Establishing effective and efficient mechanisms for monitoring, auditing and ethics review, appropriate to the design of the study.

• Provision of expert advice, guidance and training for ethics committees.

• Respecting consent and confidentiality.

• Framework for and promulgating written guidance on good research practice including publication policy and dissemination results.

• Designing procedures to ensure that funds are only allocated within a framework for good research practice ad when local systems for managing allegations of research misconduct are shown to be established and effective.

• Investigating all allegations of research misconduct firmly, fairly and expeditiously.

• Developing effective and impartial local systems for employers to manage allegations of research misconduct, including reference to disciplinary procedures or referral for criminal investigation.

• Providing access to appropriate support for whistleblowers and researchers.

Manuscript resources Committee for Publication Ethics (COPE): www.publicationethics.org

International Conference on Harmonisation: www.ich.org